Over the 2015–2016 academic year, the IHUM project New Schools brought artists into Princeton classes to devise creative experiments in pedagogy. In a workshop that followed, the participants presented their collaborations and examined what they could reveal about the artistry of teaching. What risks accompany the departure from the norms of seminar or lecture instruction, and what new kinds of knowledge might it yield? The New Schools Workshop opened a forum for thinking about the place of artistic practice within higher education, probing the potentials of interdisciplinarity for its future.

A pedagogical experiment involving artist Aki Sasamoto and Professor Karen Emmerich, with students Andra Bailard, Tess Bissell and Max Grear, was facilitated by Esther Choi.

New Schools, a project sponsored by the Interdisciplinary Doctoral Program in the Humanities at Princeton (IHUM), began from an important direction in contemporary art, work that adopts and transforms academic forms (lectures, seminars), structures (classrooms, libraries), and methods (especially archival research). The project meant to bring the pedagogical experiments of the art world back into the university, by inviting artists to collaborate with Princeton faculty to create situations within the curriculum of particular Princeton classes, undergraduate and graduate. During the 2015-2016 academic year, five artists collaborated with five faculty members in scenarios of the partners’ devising. The results of the collaboration were documented in the form of a short book of lesson plans, and whatever other records the collaborators decided to make.

A conference involving the collaborators took place at Princeton University on May 5, 2016. More about the project and conference can be found here.

IHUM New Schools was conceived of and curated by Esther Choi, Tom Mazanek, Federica Soletta, Matthew Spellberg, and Matthew Volgraff, under the direction of Professsor Jeff Dolven.

COM 402/TRA 402 Radical Poetics, Radical Translation

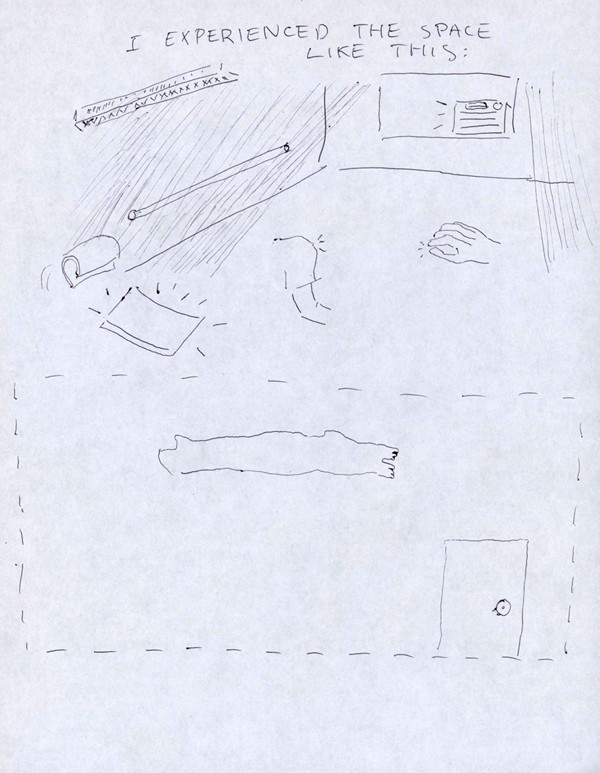

Instructors, students, and guests all participate in the activities–there are no spectators. How do we experience the subject/object of research? The goal of this lesson is to share practices with each other through hands-on experiences. Externalizing the core of one’s interest, the workshop tries to test whether research can be embodied and be translated to other bodies.

In September 2015, Aki Sasamoto presented her practice of Authentic Movements to the group. She explained that it is something she does that is related to her pursuit in art and that it is not the work she presents as a finished work. Karen Emmerich included Aki in her class discussions.

Later, in November 2015, Karen and Aki asked each student to share an activity that acts as a form of workshopping the philosophy behind her/his current research.

What follows is a group chat about the collaboration, which took place in two segments, in January and May 2016.

Esther Choi: In your initial discussions about the project, Karen and Aki, were there particular affinities you identified in your respective practices? Or thematic concerns in Karen’s course that dovetailed with concerns in Aki’s studio practice?

Aki Sasamoto: I approached Karen at a cafe just like when I meet other humans and artists–with total confidence that I have something in common with them, and something foreign and new to me. After general chatting, I asked what Karen what she does, what her course is about, and what types of topics she’s picking for the course.

Karen Emmerich: My memory is that I had been told Aki was a visual artist, like someone who made objects, and since the course has lots of visual components—texts with visual aspects that matter to the way those texts mean—I thought she could speak to that far better than I. When we met and it turned out her work is far more performative, movement-oriented, time-bound, etc., that was both very exciting and maybe a challenge for me, since it was maybe outside the concerns I usually have. Maybe for that reason, it ended up being a far more powerfully effective collaboration—one that in fact kept on going in Aki’s absence, in classroom discussions when she wasn’t around.

AS: I use language (spoken language) in my performances, so Karen’s topic on radical translation naturally interested me. But not because it overlaps with my practice, it’s simply just a basic interest.

KE: Yes! But also thinking about something that begins and ends instead of sitting there on a page was really useful. In relation to practice, I don’t even have a practice, per se. I have practices as a translator; I have things I tend to do in the classroom. Do we call pedagogy practice? What on earth IS practice, anyhow?

EC: By practice, I was referring more generally to the things that we do, as makers, thinkers…

AS: Practice is something that seems to have its shape only in other bodies. It gets fuzzy as soon as one gets asked about her own.

EC: Yes, for sure.

AS: Because from my viewpoint, you have one, Karen. And that is something we all observe in others. Maybe our collaboration focused on that. (Note: Maybe it did. Maybe we meant it. Maybe we planned it.)

KE: So, hm, just thinking out loud, but: The New Schools project. Do we conceive of it as a way of changing pedagogical practice? This is a question for Esther. Because is it then, someone comes in (Aki) and is a catalyst for something else? Which happened.

AS: This project definitely felt like a Karen/Aki meeting point. Though students got something out of it—hey, a double point.

EC: The organizers and I were certainly interested in teasing out different pedagogical possibilities, asking questions about what happens when x + y…

KE: Also z, t and m. I mean, the students and Esther.

EC: We thought of both parties (artist and teacher) as equal collaborators in that respect. Not necessarily that one swoops in and radically alters a classroom… And yes, the students were equal collaborators as well.

KE: It always feels to me in the classroom that students are catalyzing something—I walk in with my syllabus and have NO IDEA what the semester will look like. Especially this term, perhaps more than others, in the range of things I left open ended. Also, Aki is a teacher, too; let’s not forget. Boy, this is hard, once we start making people z and m and t and y and so on…

EC: Yes, for sure! I didn’t mean to polarize distinctions or roles.

AS: But we are still playing with role-play. I like that it’s role-play. I am, of course, an artist. I am, of course, a teacher. And a student. In Karen’s class, I felt that students were also so aware of such roleplaying. So I felt that we could get right into “the game.”

KE: Oh, for sure. Princeton students are good at playing the part.

EC: I thought the Jungian intuitive movement exercise Aki led in a dance studio in Dillon Gym during the introductory meeting was extremely useful in setting the tone. Especially the discussion that followed afterwards in which we were asked to describe a movement we witnessed through description without judgment. I was really surprised by how quickly the students caught on to the whole thing. There really was no resistance or skepticism.

AS: Skipping the “framework” talk and retroactively discussing its possible meaning… is such a luxurious space of teaching. Or, maybe it’s not luxury. I must assume such possibility at all times. I was hopeful that things would work. And this time, I felt we achieved a great balance. It probably had something to do with the small class size, too.

KE: The students did catch on. They do catch on. They’re totally aware at all times, I think, of how certain spaces invite certain behaviors. We, in fact, talked about those things from the very first class, before the collaboration even got going. The class size, class makeup, and the bizarreness of the classroom where we felt like we should be having some kind of lonesome banquet at opposite ends of this huge, huge table with wood paneling.

Tess Bissell : I think it helped that there were only three of us [as students] and we were all pretty down to do weird things. It might have been really different with fifteen people. I think the roles were malleable. Bringing in a guest definitely helps with that because the professor automatically becomes a student in some ways.

Andra Bailard: I think some of that acceptance may stem from the three of us all participating in different forms of art both within and outside of the classroom. It was also such a small class that we knew each other fairly well and felt pretty comfortable. It was interesting to not be tied down to that space and be in the dance studio for an afternoon. I did the exercise with Professor Emmerich one of the two times. At first I was afraid to touch her to let her know when she was going to bump into someone, but that became much more comfortable. Interpersonally, I think it helped that Professor Emmerich was as unsure what to expect as we were.

TB: The exercise was relaxing, I think. I actually felt quite at home with the exercise—we do a lot of similar stuff in the dance department! It was very difficult to describe with making any judgments. It was also weird and nice to break down the professor-student dynamic: not that Professor Emmerich was ever super formal or anything (plus there were only three of us in the class…) but taking the seminar out of the East Pyne classroom setting and into a dance studio where I was probably more comfortable than most others (except Aki, of course) was an interesting inversion.

AB: I agree with Tess about the exercise and how it changed the social dynamics within the class. Though I would also say a little challenging since it was so outside of the realm of how classes usually work. I felt like I learned an important lesson concerning the difference between description and interpretation. It was very easy to lapse into judgment (not judging whether something is good or bad, necessarily, but instead ascribing meaning to something without it necessarily being inherent to the action itself). I think that’s a lesson that extends beyond the Jungian exercise we did that day.

EC: What struck me about the movement exercise was the extreme vulnerability it necessitated. You were asked to physically interact with someone—a classmate or teacher or random guest like myself—

which we do not typically do in academia.

TB: I agree—I think the most vulnerable aspect was relying on the other person to save you if you were about to bump into someone or something. There’s something unspoken that happens in those potentially awkward and vulnerable moments where the group just decides, “okay we’re doing this and it’s weird but I’m okay with it.”

EC: I can’t help but also relate this to the notion of performance within an academic context. To really “get” the exercise, you couldn’t allow yourself to self-censor, or care what others (your partner) thought.

TB: Yes, that’s so true. And I feel like what made this seminar such a great experience in general was that it was a really comfortable environment where we didn’t worry about saying something “wrong.”

AB: I definitely felt like our second time performing the exercise was easier in that respect. I think I could let go of any discomfort that I might have had during the first time, such as whether or not I was doing the exercise “right”. I think I actually did the exercise “right” when I was less self-conscious.

EC: It felt risky to do it.

AB: I agree with that. Comfortable doesn’t necessarily mean exciting.

TB: I felt like the whole experience was kind of a risk—like it was a risk to be doing something like this in a Princeton class, which usually works in such a predictable way. And Professor Emmerich was pretty upfront about how she had no clue what we were going to do, so it was like a big pedagogical risk on many fronts.

AS: That is true to your topic, Karen: The assumption and leap that translation works.

KE: Translation works!

AS: Unless we have such a faith, we cannot utter words.

KE: And maybe also the basic assumption about classroom learning, too—it works. Sometimes better and sometimes worse but it always

does something. And the something is not always the scripted thing.

AS: Unless we have faith that a unique use of language portrays its own thought process…

KE: Theater works, too. And dance. All the things work. And it, and language, can also stick to externals, not internals.

AS: Yeah, it always works. When things break down, it also works. It works in the future.

KE: Time-lapse, time-lag pedagogy.

AS: This is why it is impossible to “measure” the effect of a plan.

KE: The time to ask people what happens is five years from now, when they’ll have forgotten…or never.

AS: It surfaces at different rates, you know.

KE: And it’s not an experiment where you can isolate factors.

AS: Unless you “practice” translation, I bet most effects will be impossible to link to the particular of the classroom phenomenon. I have an interest (in my artwork) to link causes and effects in life events or personalities. So I intentionally get into my field (life and human communication), with eyes wide open to find such links. It’s forced. I sometimes feel like I am lying or generalizing to make these links.

KE: And I, in my translation work, have an interest in linking one text to another, somehow.

AS: So I just made an assumption that translation is also “forced” through a translator’s practice.

KE: One in one language, one in another, which does not work the same way. Yes, it is, very much so. You build equivalences as you go.

AS: The forced =

KE: People tend to assume those equivalences already exist, you just call them forth, which is false.

AS: That’s the practice. Trying to make the two linked. Otherwise particles in the world scatter.

KE: The biggest impulse of the course was to question the ways in which we assume those equivalences to exist out there in the world for us to call upon… Which is why seeing someone operate in a very different way was so helpful, along with the movement exercise, where students were asked to move to impulse.

AS: Yes, I saw you question that.

KE: The impulses often ended up being already learned.

Tess Bissell: It was hard for me to move on impulse—my impulse was to do a choreographed dance warm up!

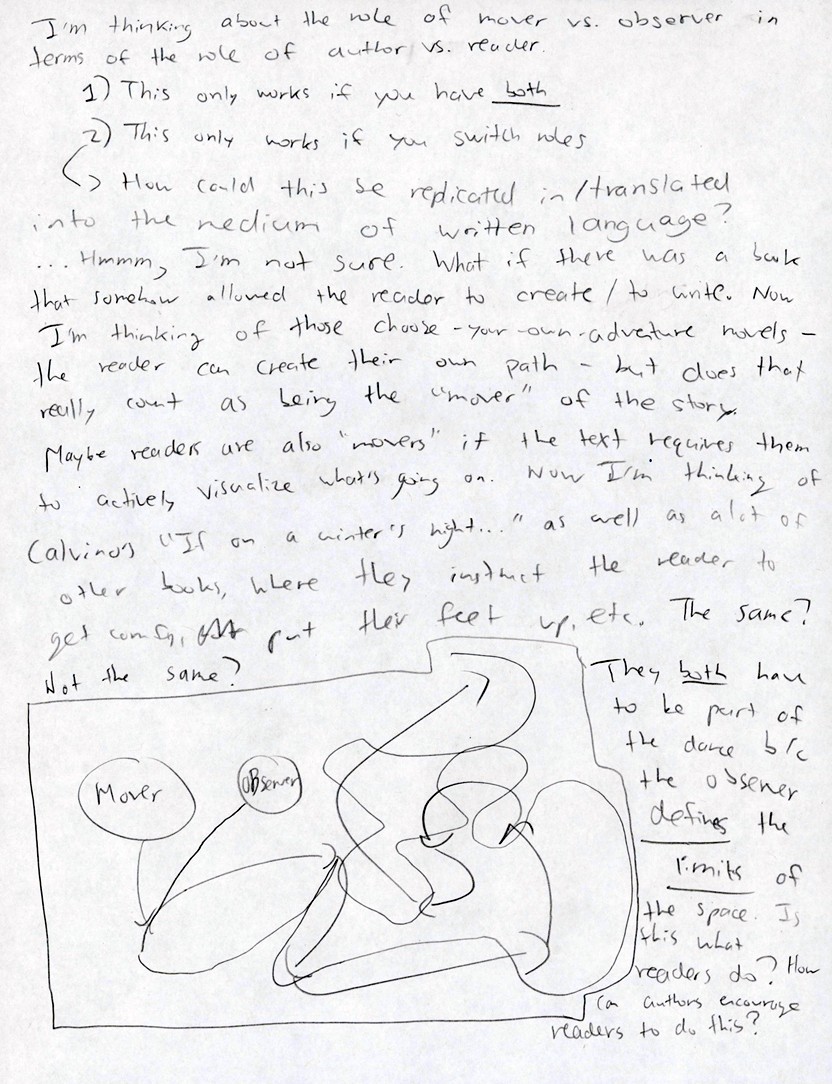

EC: Speaking of equivalences, one of the most powerful aspects of this collaboration was the way in which it introduced the body and movement into language. The students’ exercises also seemed to reflect a kind of equivalence between movement and thought/ speech. Or an interest in that.

KE: Hm, I don’t know. Equivalence means this equals that; we can shift this into that. Not an equivalence, but how do these two things affect one another.

EC: Yes, that’s what I meant.

AS: Yeah, the romantic view on “impulse” is to be suspected.

KE: But also it is in language: The idea that brod=pan=bread. We always return to that, instinctually, without thinking that this lemon might correspond to that piece of seaweed (which is a quote from Spicer that we kept returning to).

AS: Yeah, art is very useful for thinking about that. Representation always fails. (Well, I guess I shouldn’t speak for the whole of art… since some do believe in representation). So I definitely use a stand-in (water bottle) to take the role of a subject (brother). Using the body was a good exercise for thinking about “practice,” but it’s because we were not teaching a dance class. It’s a stand-in to think about language.

KE: Practice with no performance.

AS: Or practice with particular postures.

EC: Aki, can you say a bit more about how you worked with the students while they formulated their exercise? It seemed there was a focus to actively integrate movement into their projects.

AS: Karen and I were very open to what may happen after the initial movement exercise and my participation/ observation in her class. We talked about possible scenarios of Aki performing and using that as a subject to translate… or other ideas I’m not remembering…. but after the September visit, due to the size of the class, and due to the participants’ understanding of “role play,” I proposed to extend the movement exercise to this whole class. It rather happened organically. Thanks to Karen’s open-endedness, and Aki’s whatever-goes attitude.

KE: And then during our last class session, the students assigned the “reading” for the class. Some of the reading was listening/watching.

AS: Karen asked students to come up with workshop ideas. Then Aki responded to the students’ plan via email and made some suggestions.

KE: I.e. again the problem of measurement of effect, what comes from where.

AS: I was super excited about that. Because I didn’t have expectations what it would be.

EC: I’m curious as to how you each imagined movement or performance—that is, thinking about language through the matrices of affect and time—would change the dynamic of these exercises or readings.

KE: I stressed that their workshop should have active components.

EC: But did you each have an idea of what this might achieve—how it might change our relationship to translation or social interaction, and so forth?

AS: Karen has been pushing their brain button to see “active” components of texts. So I think it was not a difficult leap to involve activation.

EC: Andra, perhaps you could relay your experience of working with Aki to put together your exercise for the class?

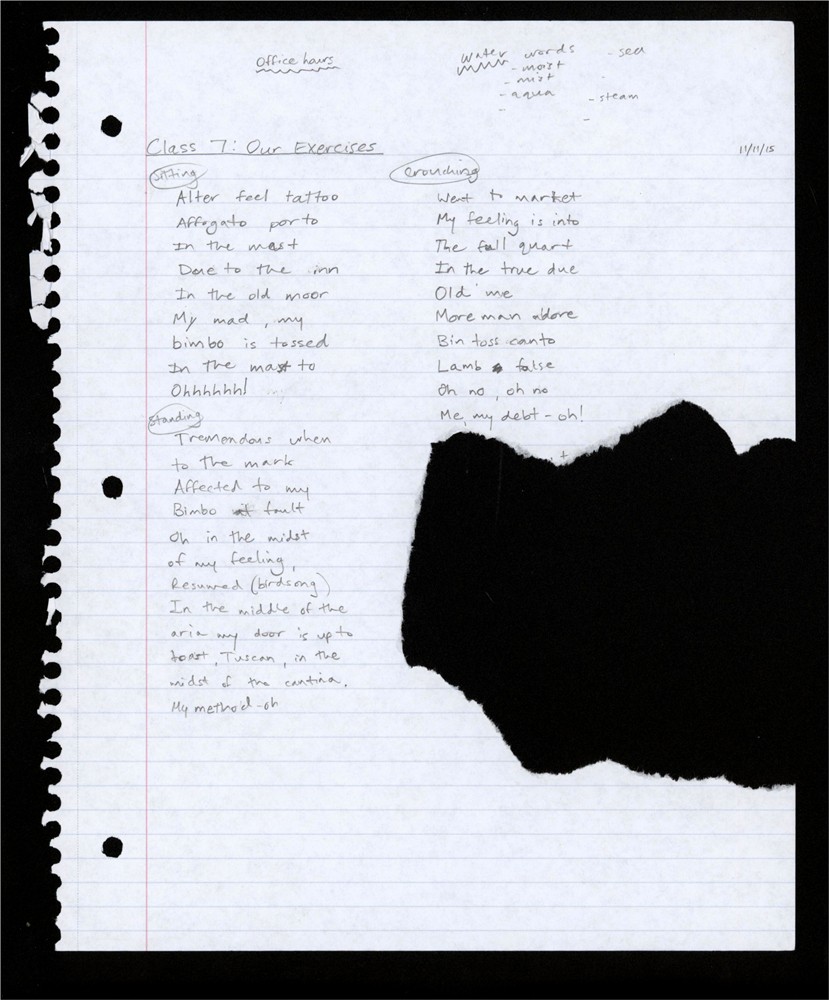

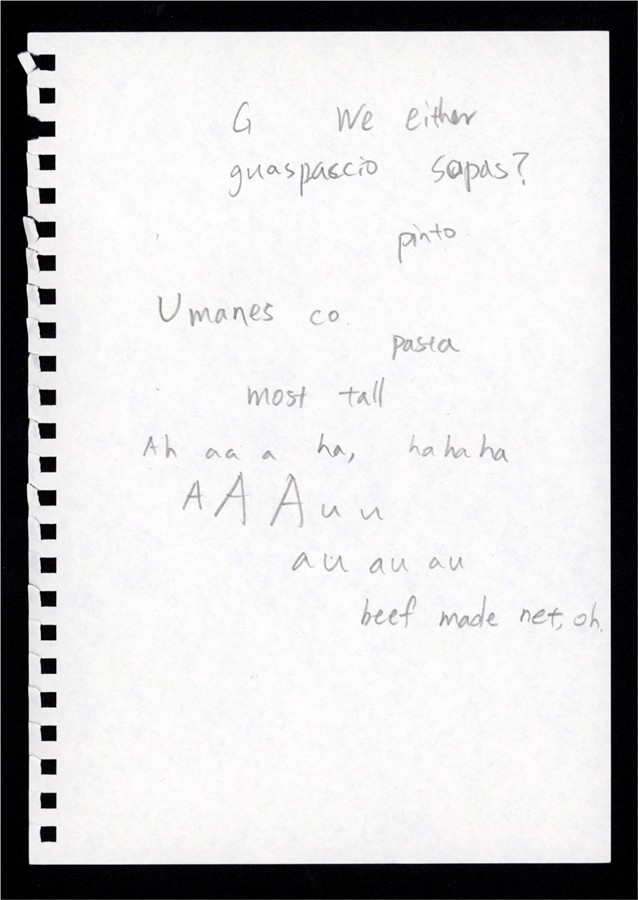

AB: Aki and I interacted over email. Aki provided a lot of possible variations on my activity, and her suggestions included using props like eye masks or headphones as part of the exercise. It was her suggestion to incorporate movement into the homophonic translations, and I ended up following that route because I liked its connection to our experience in the dance studio. After that I really wanted to have the opportunity to get up and move within a traditional classroom space. I think one thing that we discussed in class a few times was the idea of texts existing within a context, and particularly translations that are iterations of other texts, inextricable from the language and cultural assumptions of their time period. I don’t entirely separate texts from events in my head to begin with because I consider each reading to be a new experience of the reading material. It’s always seemed to me that each time we read something, our experience is informed by our previous readings of the text, but also other experiences and things we’ve read in between readings. I think that was where I was coming from with my exercise. Some of my interest in that stemmed from taking a social psychology class that semester and thinking about how our environment changes the way we think and behave. During my exercise, I asked everyone to listen to an Italian song (“L’altra notte in fondo al mare” by Arrigo Boito) and to do a homophonic translation (essentially, an English transcription) of the lyrics they heard. I then asked us all to change our body positions (for example: sitting, lying down, standing) and do the exercise again, hoping that moving our bodies might change the way we experienced the song.

EC: It definitely seemed as though integrating movement into the act of working with language allowed us to return to a place of vulnerability and impulse.

AB: Plus, I was thinking about different levels of comfort when we read or otherwise experience a work. Sometimes when I’m doing my reading for classes, if I’m sitting in an uncomfortable position, I may retain less or feel differently about what I’m reading than I might if I was reading in a comfortable chair/position. “Impulse” is a great word for that.

EC: …Which affected how comfortable we felt with engaging in the homophonic translations.

AB: Which are out of a lot of people’s comfort zones as an experimental means of translating, especially for those who don’t know the

language they’re transcribing from.

EC: Comfort and vulnerability are issues that seem to have been important to Max’s exercise as well, which centered on issues of digital privacy. His exercise asked participants to work in pairs and create “joint accounts” together. This process required sharing personal, intimate information to craft a series of security questions that only the pair could answer.

KE: In Max’s exercise I think the very fact that he wanted logins to happen in pairs is some kind of thinking about collaboration, that vulnerability that wouldn’t have happened in a static classroom. A classroom isn’t really a place where things can be foreseen. I mean, it’s like asking leading questions. If you ask a question and have an answer in mind, you might as well just make it a statement, not a question.

AS: I love open-assignments. I mean, open in terms of shapes and contents of the works. I hate statements in teaching.

KE: I hate statements disguised as questions.

AB: I appreciated that everyone, including the students and guests, participated in my exercise. I think what differed from other times when students lead the class was the fact that we got to determine what exactly everyone would be doing, instead of just following a rubric or plan provided by the instructor.

EC: Do you think this type of collaboration could only ever be framed as an experiment?

KE: I’m not sure I understand. Isn’t all teaching always experiment? At least in terms of not knowing the result?

AS: No. To me, this is usual. Nothing heroic.

KE: Ditto. The methodology is always experiment/ not knowing!

AS: It’s not fixed. Although we practice, and it may start by looking like that. We should break such assumption when that starts to =.

EC: I was struck by how experimental and personal the students’ final projects were. I wonder if the highly subjective format of the movement exercise somehow made this “okay” to do, though I also got the impression that the course as whole was very open to it.

AB: Yes, which is why I think the exercise ended up working well in the context of our class. I guess being able to break out of the traditional classroom set up may make students less afraid to make “mistakes” and to take risks, and I think “mistake” becomes a very subjective idea.

TB: Maybe! I think it definitely contributed to a sense that Professor Emmerich was already cultivating, that she wanted the classroom to be a sort of experimental laboratory, and that we were all partners on that adventure (rather than a prof leading and us following behind). I wish more classes were like that.

EC: This brings us back to the idea that classrooms aren’t really a place where metrics can be applied, that is, one cannot necessary measure the effects of a particular exercise or strategy etc. This notion about pedagogy seems to be in alignment with the prompt of the first exercise that Aki led: description without judgment.

TB: I agree: it’s the idea that your classmates and prof are a sounding board rather than people there to say if you’re right or wrong. Or that just by verbalizing something you can find new things and ideas. The New Schools exercises brought a feeling of creative freedom to the class, so I felt like I could go for it and do something different (i.e. not a paper). For the final project, I created a podcast: I conducted about ten interviews of family members and friends, in which I asked them questions about the Araki Yasusada hoax and the concept of pseudotranslation generally, and curated their responses (and my own thoughts) into an hour long podcast.

EC: Do you think this experiment runs counter to the notion of writing a lesson plan, then?

KE: I’ve never done lesson plans—my lesson plans are usually three names with circles around them.

AS: You need to have a general direction, and be firm with the first stone to throw. But you need to be ready to form the next thing as things unfold.

KE: Yes, and also the syllabus is one grand lesson plan. It’s just on a different scale.

EC: I suppose what I’m getting at is how we might tease out the relationship between drafting a script versus allowing contingency, novelty and invention.

AS: The syllabus and exercise outlines are tools for the class. But real interactions are immeasurable and unrecordable.

KE: That is the grand question of all teaching, and Aki’s answer is spot-on.