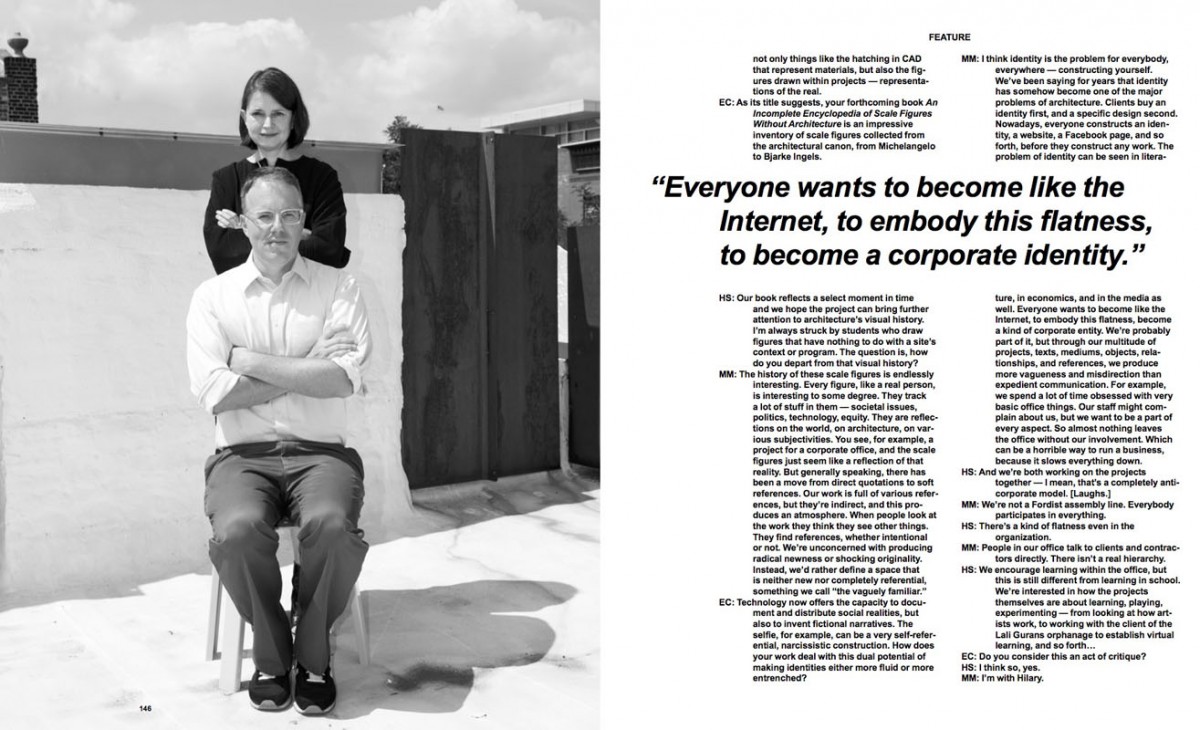

This conversation with Hilary Sample and Michael Meredith took place in MOS's office located in Harlem, New York, on August 5, 2016.

Since starting their office in 2003, Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample, founders of MOS, have quietly evolved from architecture’s best-kept secret to become two of North America’s most influential young architects. Their brand of playful conceptualism has made them a favorite among academics and clients alike. From their residential projects (Floating House, Canada, 2008 and Element House, New Mexico, 2014) and museum installations (MoMA/PS1, Afterparty, 2009), to their retail spaces (Chamber Gallery, New York, 2013) and educational institutions (Krabbseholm Højeskole, Denmark, 2012), their work exudes a naïve simplicity that belies the precision and complexity of its details and finishes.

It’s an approach to digital aesthetics that Meredith and Sample have honed over the years, finding innovative forays into all aspects of their practice. Take, for instance, their renderings, which celebrate their cartoonish incompleteness and scalar ambiguity. With a copy-paste feel, archetypical architectural elements like chimneys, corridors, and pitched roofs are mixed freely into various aggregations. Meanwhile, their scale figures adopt the innocent guise of children’s book characters (inspired by the work of late children's author and illustrator, Richard Scarry) to cleverly veil the social identities they wish to critique.

Indeed, Meredith and Sample are keenly aware that the humility and humor of MOS’s sensibility stands in stark contrast with much of the heroic posturing so common among architecture’s status quo. Both have a long history of writing and teaching (Meredith at Princeton, Sample at Columbia). Always questioning, their approach is equally a reaction to the sedate traditions of previous generations, and a product of their continual engagement with new sets of concerns.

Experimentation also seeps into the work ethic of MOS’s Harlem sleeper cell of an office, located in a four-story townhouse, divided in two. While their private home is located on its top two floors, the lower floors function as a laboratory for their myriad in-house productions: In addition to their ever-growing architectural practice, software experiments, films and book projects proliferate on a continual basis (an exhaustive research tomb on the history of scale figures was published this year). More recently, they have expanded their repertoire to produce satirical reproductions of home décor items, furniture and housewares, such as a candle by Adolf Loos, or an O.M. Ungers “Almost Positivist” cutting board.

But make no mistake: this is no mom-and-pop operation. Despite their eclectic, “everything all at once” approach, which is also happens to be the title of their first book, MOS has retained a sharp focus. Indeed, these days it seems that everything is happening all at once, too: With three important awards in 2015 alone (the National Design Award from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; and two from the American Institute of Architects), along with invitations to participate in prestigious architecture competitions, MOS is slowly elbowing its way into the big leagues.

It’s a good time as any to check in with Meredith and Sample to discuss cultural hyperbole, the current zeitgeist for flatness, and how it all began.

Esther Choi: You were both went to undergrad at Syracuse University in the mid-1990s. By the time you finished grad school in the early 2000s, architecture was preoccupied with what you’ve described as a “parade of novelty” — a fetishization of computational technologies. Can you describe that generational moment?

Michael Meredith: The explosion of the digital as an architectural problem is a very “American” problem that occurred in the late 90s. It was the beginning of the computer taking command. Both Hilary and I grew up with computers, video games, etc.... but our professional training started with hand-drafting and hand modeling. The computer was there, but if you were a serious architect you’d try to avoid it.

Hilary Sample: Computers appeared at the studio desk yet we were never formally trained in how to use them. In a way this informal relationship to them engendered a total sense of freedom; we could pick and choose the things we were most interested in learning. As a result, we were really self-taught.

MM: In those early days technology seemed more democratic and software circulated freely. You could download self-tutorials and learn video editing or music mixing software. Consequently, there has been a ridiculous expansion of skills in the profession. Going from hand-drafting to parametric modeling to engineering analysis to photo-realistic rendering to scripting, or coding, the architect’s skill set exploded.

EC: How did that shift in education translate into the reality as a working architect?

MM: When we came to New York we both had to start all over again. I graduated from Harvard in 2000 and the economy was just horrible. For months I would walk around with a resume, door to door, to get a job. You’d show up to someone’s office and stand there with your resume and people would give you sad looks like, “So sorry, can’t help you.” It was a humiliating experience. When I eventually found a job I was quickly disillusioned by the realities of the profession. So I started volunteering at places like Storefront for Art and Architecture where Kyong Park and Shirin Neshat took me in. I helped out however I could. We’d do competitions. And we’d make all sorts of books and we’d sell them through Printed Matter.

HS: When I graduated from Syracuse I first decided to move back to Easton, PA, the area where I grew up. I had a chance to work in an office that was building things at the time — not a lot of people were doing that. The projects weren’t extraordinary but it gave me the chance to really build things and to learn how to do the kind of basic things that architects do. I felt that was really important as a woman in architecture to have that opportunity. I’ve always been interested in making buildings — to really do something from the ground up. I was also really worried about coming to New York and winding up doing interiors. Not to harp on the gender thing, but to me it really felt like I could easily see getting trapped and never being able to get out.

EC: You’ve come a long way since those early days. Going from small installations to single family homes and artist studios, to now working on much larger-scale works such as Lali Gurans Orphanage and Learning Center in Nepal or being invited to the Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study competition. How do you approach the growth in scale and scope of your buildings?

HS: Our office is rooted in an American model of practice, which typically begins with the single-family house, working through smaller scale projects towards larger projects. In some ways this is a natural progression, and we prefer projects that have a human scale. And while we usually don’t have the luxury of picking our work, we think about our trajectory as much as one can in this profession. That’s why it was such a privilege to be invited to a recent competition for the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Not only because we were competing against so many offices we admire, such as OMA, Steven Holl, or Tod Williams Billie Tsien Architects, but also because we’re deeply interested in education and spaces of social and cultural exchange.

EC: How do your smaller-scale projects, such as the objects, fit into this trajectory?

MM: For our first book we looked at the cultural situation of “everything all at once,” 1 and we are still very much interested in this idea of working across media and relationships, while also building this playful sense of discovery in our work. We still get strangely as enthusiastic about designing things like a coat hook or stool as a retail space or an art studio, school, or housing. But even with this variety, we still want to construct a consistent body of work. It’s a very slow process to construct an identity or voice in architecture. Even if it’s polyphonic or multiple, it needs to hold together. We are getting closer, but not there yet.

HS: I’m not sure if we’ll ever get there. [Laughs.] But for us it’s all about making a series of things and referencing previous things we’ve made. After 13 years we’re no longer starting from nothing. Every time we begin something we’re dealing with the things we’ve already made while also inventing new ones. If you look at Krabbesholm Højskole [2012] for instance, invention comes in the organization of the buildings, but also in the detailing between the cementitious panels, the width of a gap, by paying a little too much attention to a mundane detail. We establish ideas through models, drawings, video, sketches, and texts and then these things start to inform each other.

EC: You’ve recently published a short essay about a sense of “flatness” that is pervading architecture and culture alike in El Croquis [No. 184, 2016]. How does this “everything all at once” situation, where you’re working in multiple scales, media, and formats, relate to your theory of flatness?

HS: The idea of flattening means that more things are accessible. It’s not like when we were students, when there was a limited set of rules you had to subscribe to, and you’d sneakily have to learn about projects through magazines to have alternative things to look at. The Internet wasn’t what it is now.

MM: Nowadays, everything goes. It could be an amazing, liberating moment. Or, in the worse case scenario, a popularity contest. In the absence of discourse, people judge the work in terms of the quantity of an architect’s projects or the size of their online following. Popularity seems to produce more popularity. Recently we started to use Instagram. Once you get into that world, it is hard not to think of architecture as a competition of likes. You can get sucked into it, even with the best intentions.

HS: But you could say that was always the case, even with Le Corbusier, Mies, or Frank Lloyd Wright. They always had a lot of work, or were popular with certain audiences. Though for an architect like Mies, exploring structure and material was considered sufficient grounds for practice. Today that view, for some, is too removed.

EC: In the era of Mies & Co. you needed a reputable historian like Siegfried Giedion to “verify” the work’s importance, but Instagram legitimizes through consensus. Do you think there are issues with architecture turning into a citizens’ affair, regardless of one’s expertise or critical engagement?

HS: Yes. Today, celebrating leisure is enough for a lot of architecture practices, by selling stuff to people that doesn't make you think. We hope our work has a measure of self-consciousness to it. That self-consciousness hopefully makes it more social.

MM: Our current culture is hyperbolic, at every level— a kind of life hyperbole and an architectural hyperbole. That’s a problem of the flatness of the post-digital world. You want to resist or avoid a total dissolution into the flatness of the field, but this is what would be desirable from the perspective of the market. For the market, it’s ideal to be completely malleable, maybe while maintaining just enough identity for a brand.

EC: There is a great essay by the American art historian Moira Roth, which you’ve also referred to in the past. It’s called “The Aesthetic of Indifference,” (1977) and in it she argues that a number of artworks embody a particular American mindset during the McCarthy era — a pervasive alienation and a paralysis on the part of liberals to actually engage in action. Is there a relationship between “The Aesthetic of Indifference” and this contemporary flattening that you’ve identified?

MM: I think that this indifference is, at some core level, integral to Modernism and Postmodernism. If you look at early Modernism, Albert Camus is constantly described as an indifferent writer. Short sentences, distant. Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari — there is a kind of flatness of attention. You can find it everywhere. Even Edouard Manet is always looking to the left of the aristocrat, toward the servant, off-center, somewhere else. It’s in all the stuff we like. This not-looking at what you’re supposed to look at, or doing the counterintuitive thing. Moira Roth’s essay is a cautionary tale, to remind us of the limits of indifference — like how Venturi, Scott Brown accepted everything, to the point where their work became inseparable from Reaganomics. At the same time, we totally disagree with Roth’s understanding of politics in art. She seems more interested in the aesthetics of politics. We are interested in the politics of aesthetics.

EC: Is that how you would describe the way your work resonates?

MM: I think it’s a tone. Maybe a monotone. [Laughs.] The work comes out of a situation: this office, the people, our teaching, friends, colleagues, a book, an album, random stuff on the Internet. There’s a kind of culture that we are interested in trying to produce in the office, but that is also producing us. There’s not a method, but there are values. And I think even the rule set that we put together for El Croquis [No. 184, 2016] is more about values than rules. The rules are very vague, such as “We’re interested in non-composition,” or “Pursue the deadpan and the vaguely familiar, not the shockingly new." Of course, what that means is really up for grabs. [Laughs.] Behind a statement like that are classic, almost avant-garde, values. They’re not really ours; they’re part of an idea of a discipline that we’re trying to recoup.

EC: I would like to talk about your renderings. In contrast to the aspiration of most architecture renderings that attempt to show us some photo-realistic version of what life is supposed to be like, yours celebrate incompleteness and scalar ambiguity, which can also be found in your models. There is a copy/paste feel to your assembly of archetypal architectural elements — chimneys, corridors, pitched roofs…

MM: We try to have fun, to play within architecture. There are strange relationships between our texts, the objects, and the software experiments. It’s not a one-to-one relationship between things. Somehow we put them together and something happens. It’s more alchemical, and maybe that act inherently has a kind of political indifference, or a surrealist absurdity to it, but they’re also impossible to separate from each other. In 2014 we wrote a tiny text about the Element House [2014], a little blurb called “Systems and Shapes.” And all of a sudden, people started to look at our other projects through the lens of that text. That’s one of the feats of the good architects that we admire — when you look at their work, you’re already thinking about other work or other things that are related to it. It’s never just looking at it. That is what we aspire towards, I suppose.

EC: In his book on the concept of soft power2, the political scientist Joseph Nye compares the political model of top-down coercion with that of co-option, where appeal has more influence. Do you see a parallel between the way you work and this idea of soft power?

MM: It might sound a bit corny, but inclusivity and openness are simply part of how we engage the world, and our work. Hopefully this is both a formal and utopian project. We want to make the world better, but we don’t work through direct action. We’re always distanced by the fact that we represent architecture, and don’t build it all ourselves. We only build fragments or components — tiles, bricks, and elements. But that said, we produce things that, in turn, construct attention, discussion, reflection, and we do this not with one grand masterpiece statement but through a collection. We work within our increasingly diffuse world of ever-growing stuff, histories, texts, websites, feeds, and opinions. For example, we are making scented candles to discuss some longstanding prejudices in the discipline such as, Loos vs. Hoffman, or conceptual vs. commercial. There’s a model of critique in there, but it’s a soft critique.

HS: I have no problem saying that as a woman in architecture I have a different viewpoint of the profession, the discipline, its history, of what we’re supposed to be doing, of our tasks and responsibilities in the world. It’s one of the concerns of my book, Maintenance Architecture [MIT Press, forthcoming 2016]. We should have a certain set of concerns that go beyond flatness for its own sake — that reach beyond — but enable coming back into architecture to change it for the better. For example, in our early education we were given a set of rules, and we weren’t supposed to be concerned with who would actually be in your architecture. The human body was removed from the drawings, from the axonometrics, from the images of architecture. So now we overly-populate our projects with seemingly weird, yet vaguely familiar people. [Laughs.] But interest in how the projects are actually inhabited has led us to rethink not only things like the hatches in CAD that represent materials, but also the figures drawn within projects — representations of the real.

EC: Your forthcoming book, An Incomplete Encyclopedia of Scale Figures Without Architecture [MIT Press, 2016], which, as the title suggests, is an impressive inventory of scale figures collected from the architectural canon, from Michelangelo to Bjarke Ingels. I was struck by the dominance of male architects.

HS: Yes. The architects are predominantly male.

MM: It’s definitely an issue.

EC: How do you think the lack of women architects in the catalogue speaks to our current moment?

HS: There is still a shortage of women in architecture. Not so much in schools, but in practice, especially those with licenses. Our book reflects a select moment in time and we hope the project can further bring attention to architecture’s visual history. I’m always struck by students who draw figures that have nothing to do with a site’s context or program. The question is, how do you depart from that visual history?

MM: The history of these scale figures is endlessly interesting. Every figure, like a real person, is interesting to some degree. They track a lot of stuff in them — societal issues, politics, technology, equity. They are reflections on the world, on architecture, on various subjectivities. You see, for example, a project for a corporate office, and the scale figures just seem like a reflection of that reality. But generally speaking, there has been a move from direct quotations to soft references. Our work is full of various references, but they’re indirect, and this produces an atmosphere. When people look at the work they think they see other things. They find references, whether intentional or not. We’re unconcerned with producing radical newness or shocking originality. Instead, we’d rather define a space that is neither new nor completely referential, something we call “the vaguely familiar.”

EC: Technology now offers the capacity to document and distribute social realities, but also to invent fictional narratives. The selfie, for example, can be a very self-referential, narcissistic construction. How does your work deal with this dual potential, to either make identities more fluid, or make them more entrenched?

MM: I think identity is the problem for everybody, everywhere — constructing yourself. We’ve been saying for years that identity has somehow become one of the major problems of architecture. Clients buy an identity first, and a specific design second. Nowadays, everyone constructs an identity, a website, a Facebook page, and so forth, before they construct any work. The problem of identity can be seen in literature, in economics, and in the media as well. Everyone wants to become like the Internet, to embody this flatness, become a kind of corporate entity. We’re probably part of it, but through our multitude of projects, texts, mediums, objects, relationships, and references, we produce more vagueness and misdirection than expedient communication. For example, we spend a lot of time obsessed with very basic office things. Our staff might complain about us, but we want to be a part of every aspect. So almost nothing leaves the office without our involvement. Which can be a horrible way to run a business, because it slows everything down. [Laughs.]

HS: And we’re both working on the projects together — I mean, that is a completely anti-corporate model.

MM: We’re not a Fordist assembly line. Everybody participates in everything.

HS: There’s a kind of flatness even in the organization.

MM: People in our office talk to clients and contractors directly. There isn’t a real hierarchy.

HS: We encourage learning within the office, but this is still different from learning in school. We’re interested in how the projects themselves are about learning, playing, experimenting — from looking at how artists work, to working with the client of the orphanage to establish virtual learning, and so forth…

EC: Do you consider this an act of critique?

HS: I think so, yes.

MM: I’ll go along with Hilary.