An article that probes Studio Formafantasma and London-Based Dzek's experiments in testing the architectural limits of volcanic ash.

Earlier this year, Sicily’s Mount Etna began to rumble. It heaved a thunderous roar. Smoldering volcanic ash spewed high into the air. Cascades of red molten rock poured from its mouth and down its slopes. This wasn’t the first time the volcano had shown its ire. It erupted in 2013, shooting tufts of smoke into the sky and showering the surrounding villages with black earthen debris.

Standing at 10,922-feet, Europe’s most active volcano has a well-established reputation for its unruly temper. Its 1669 eruption made history by completely reshaping the island’s coast. In the early 1980s, and again, in the early 2000s, Etna’s mountainous hiccups were responsible for destroying thousands of acres of woodland, homes, villas, and vineyards. Yet Sicilians have also benefitted from Etna’s fury: a byproduct of the volcano’s presence is Sicily’s resource of fertile soil, upon which the island’s olive trees, orange groves, vineyards, farms, and villages depend.

For Andrea Trimarchi, half of the acclaimed design duo Studio Formafantasma, the volcano has been a benevolent presence since childhood. “I was always fascinated by it; it’s a beautiful landscape,” he says to me one afternoon in late-August. “Back then, it was effusive so you could get close to it and take material directly out from the mouth of the volcano.” Etna’s testiness has cultivated further inspiration decades later. The newest chapter in the designer’s dance with this unwieldy volcano has involved a number of experiments with its lava in collaboration with Dzek, a materials development company based in London.

When I travelled to Columbus, Indiana, to discuss Formafantasma’s desire to transform lava into a building material, I found Andrea with Dzek-founder, Brent Dzekciorious, sprawled on a lawn, under a tree. They had just finished installing “Window to Columbus”, their featured piece for Exhibit Columbus—the first unveiling of their volcanic ash experiments. Taking the form of a wall made of glazed bricks that glistened in the afternoon sun, the dark structure was both familiar in its relationship to the surrounding architecture and otherworldly. They took a moment to catch their breaths.

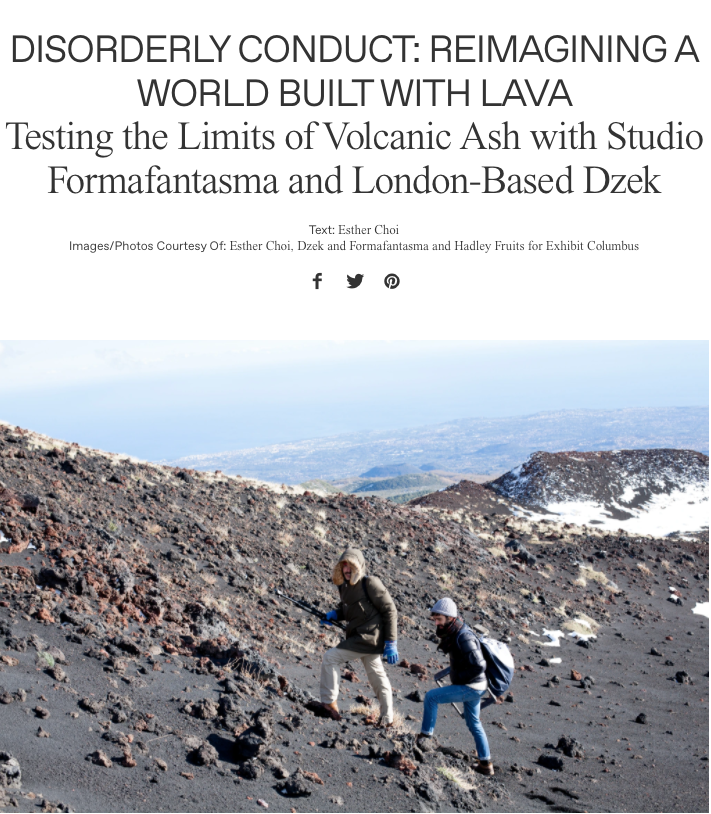

Meeting with Andrea and Brent, it was clear that lava’s mercurial moods had put them through the ringer. Over the course of two years, their rigorous testing had taken them from Turkey to Italy to England. Their newest venture involved rethinking the locality of the material itself, to work with basalt sourced from Scotland and tiles produced in Stoke-on-Trent. Etna had taken them on a journey beyond what they had envisioned, but I sensed the uncertainty of the enterprise was addictively enervating.

In 2010, when Andrea took Simone Farresin (the other half of Formafantasma) to visit the volcano, he had no idea how Etna’s moody nature would eventually reanimate his life. Teaching at their alma mater, the Design Academy Eindhoven, the pair had begun building a name for themselves in the international design community. Their conceptually driven and elegantly constructed rugs, chairs, ceramics and installations used everyday objects and craft processes as apertures to carefully explore the intersections between local cultures, social and political systems, history, and concepts of nature. During this trip, they traversed the volcano’s landscape of ominous black rock. A lava ashtray found in a souvenir shop made by pouring the molten rock into a metal mold piqued their interest. They were fascinated by how the material became an object almost immediately.

Over the course of several years, with encouragement from their gallery, Libby Sellers in London, the duo embarked on intensive research into the use of the volcano as both a material and facility for design production. Describing it as a “mine without miners,” Andrea and Simone saw the volcano as a self-generating system that periodically eliminated its own waste. When entire villages and the landscape’s verdant foliage were covered in a thin veil of lava dust after an eruption, residents would sweep up the dust with a broom and place it in their gardens to cultivate soil. “It’s an entity that is throwing away material,” Andrea mused. The volcano’s phases presented an opportunity to rethink the relationship of designer to material. Instead of purchasing ready-made materials, they found themselves acting as an extension of the natural cycle by shepherding the self-cleansing system of the Earth.

The result of their rigorous research and material testing with the Volcanologist Centre of Catania (INGV) was titled ‘De Natura Fossilium’ (2014), a series of geometric stools, coffee tables, and a clock, produced from sampling, melting, molding, casting and milling the lava in its various forms, from basalt stone to volcanic sand. Characterized by an impenetrable black finish, the eerie seduction of these objects—often composed with brass elements, Murano glass, textiles, and lava rocks culled from the volcano’s terrain—flaunt their shadowy, alien status of operating both inside and outside the registers of our time.

But make no mistake. Despite the objects’ formal sophistication and their coquettish gallery appeal to collectors, the material was, in Andrea’s words, “a nightmare.” The task of disciplining an undisciplined material posed innumerable challenges. The lava’s varied composition of metals and oxides required endless experiments and alterations into processes with few precedents. Firings would essentially destroy facilities. “What we ended up having to do was completely different from what we originally thought—the material behaved as it wanted to,” he explained.

Like the magnetism of lava, the law of attraction brought in new players. As a self-proclaimed “designer advocate”, Brent’s career in design collection and curation enabled him to identify a lacunae in the commissioning process between designers and design producers. Although the edition market enabled designers the chance to explore novel ideas through smaller runs, the knowledge produced in their explorations with unconventional materials and experimental processes seldom had other outlets. “I feel like things just ended abruptly in so many instances with so many projects that I was either directly or indirectly involved with,” Brent says. “Within those projects a lot of brilliant ideas live and die. I wanted to create a company that could extend those ideas and have more depth of application.”

Material development was an untapped area for creative intervention. “It’s the vehicle from which everyone creates something,” he told me. He formed Dzek in 2013, turning to young, contemporary designers he admired who were simultaneously interested in the stratum between craft and broader fabrication methods. But in an era of big box stores where large building material manufacturers have evaporated craft traditions and automated the processes of manufacture to produce standardized and often cheap quality products, Dzek’s ambitions to produce innovative materials was no small feat.

Dzek’s inaugural material, Marmoreal, was a large terrazzo aggregate created in collaboration with British designer Max Lamb and was originally inspired by Lamb’s “Quarry” (2009), a series of seating and tables created out of angular and sculptural granite assemblages. The challenge was to see how Max would approach the creation of a manmade stone devised on his own terms, rather than samples taken from the earth. The resulting recipe for Marmoreal was an iconic material that, like lava, feels transhistorical. Although its process evokes fifteenth century craft traditions, and its palette winks at Memphis postmodernism, its random patterning has a resolutely contemporary feel. Marmoreal’s ability to capture our cultural sensibility has been met with much fanfare, appearing in applications as varied as bathrooms and furniture design throughout the world.

Despite lava proving to be a more unstable collaborator, the designers were unfazed. Brent’s eyes lit up when discussing the myriad uses of volcanic matter and the countless iterations of testing they had embarked on. Andrea also exhibited a Zen-like patience upon reflecting on the process. “It requires a lot of time and trying things out,” he said. “It’s part of the game. You need to listen to the material.” Brent nodded in agreement. “The material has its own ideas of what it wants to be and can be,” he added. “It’s about understanding the balance between how much we can actually control something.” Failure was an inherent and exciting part of progress.

They were both eager to discuss the complicated theoretical, ethical, and practical concerns raised by their investigation. For instance, how their experiments with volcanic ash interrogated systems of production, locality, ecology, and standardization. Or how their struggles with lava inherently brought up historical precedents, like the use of volcanic matter in Roman concrete and its architectural uses in Sicily’s villages and towns. I suggested that their collaboration was, perhaps, part of a much bigger move on the part of a growing number of young designers, to view material exploration and process as means to interrogate and disavow the established standards of our industrialized society. This was an opportunity to declare a new standard based on a more egalitarian integration of values, economies and ethics.

We went back to the topic of having to learn to listen to the material, of understanding the lava’s agency and working with its behaviors in a cooperative mode. My mind went to the variegated surface of the volcanic glaze, with its flecks of color that mimicked Sicily’s landscape: the golden hues of the island’s center, the dense forests found higher in altitude, and the ominous black rocks that characterize the volcano’s presence. An immense, diverse beauty which reflected Etna’s multiple personalities. I couldn’t help but consider the numerous faces that volcanic matter can adopt, from matte black volcanic glass to the speckled bricks in Columbus. These relationships seem nested in each other, as an attractive appeal to a more holistic sense of relationality with nature’s processes, forms and materials.

Our lost connection to the source of our materials is affecting the foundations of our urban centers, both literally and philosophically. And the global pace of construction continues to grow. In his book Making the Modern World (2014), the Canadian scientist Vaclav Smil presents an alarming statistic: from 2009 to 2011, China’s cement consumption exceeded the total amount of cement used by the United States in the entire twentieth century. Fueled by a global economy of mass produced, resource-depleting materials with built-in obsolesce, this unsustainable enterprise begs for designers to reimagine the aesthetics and ethics of building, quite literally, from the ground up. Rather than being left in a fit of despair, experiments like Formafantasma and Dzek’s courageous parlay with nature’s waste give us hope, while underscoring the necessity to embrace risks. As their experiments with volcanic matter can attest, nature’s resistance to accepting our catalog of mechanized and efficiency-driven desires is an important reminder of our own susceptibility under the tyranny of its power.